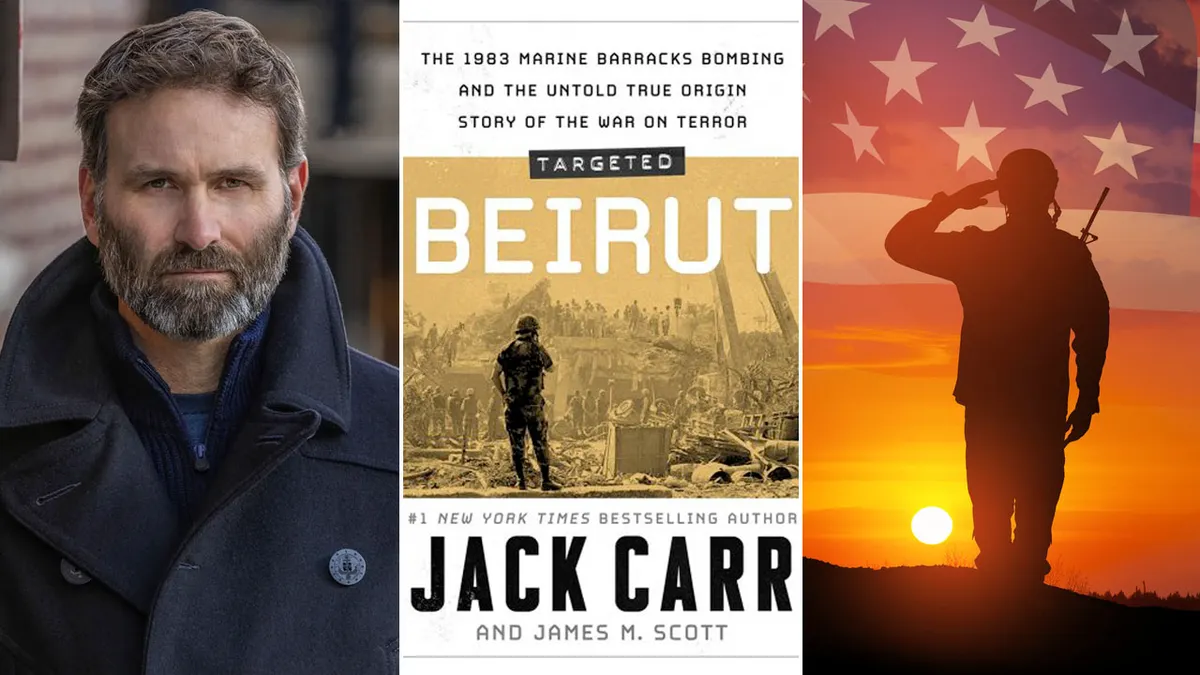

FIRST ON FOX: Editors' note: New York Times bestselling author and former U.S. Navy SEAL sniper Jack Carr has teamed up with Pulitzer Prize finalist James M. Scott for a series of nonfiction books that explore key terrorist events around the world that changed the course of history.

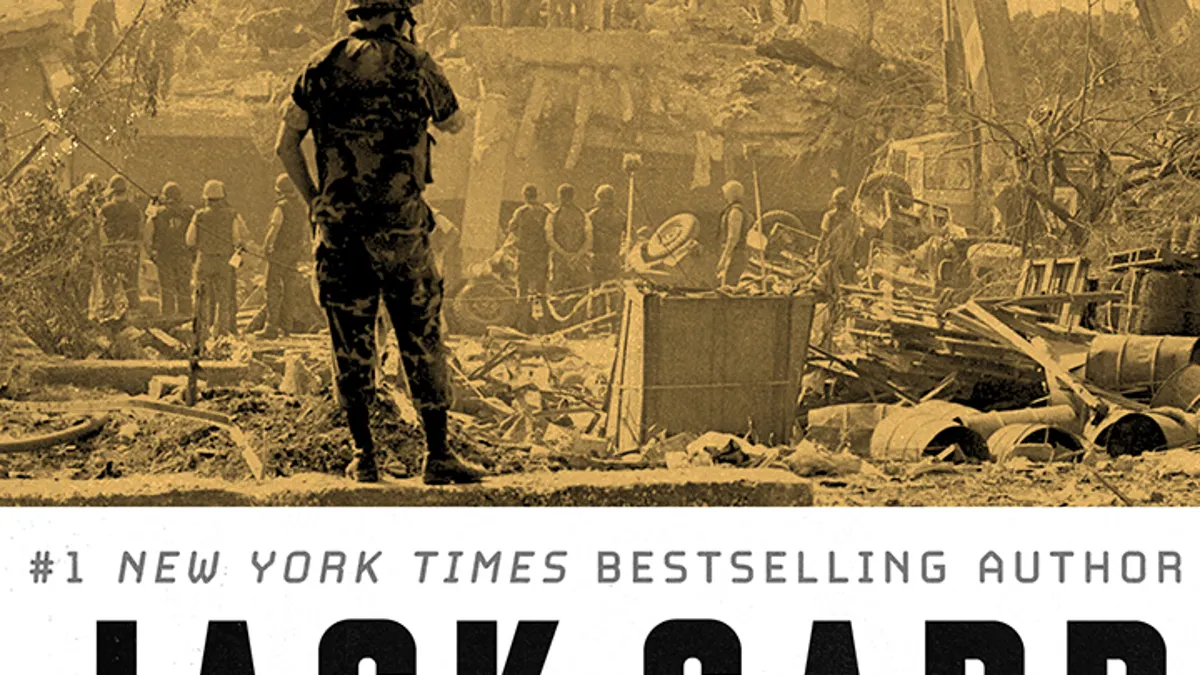

The first book in the series, "Targeted: The 1983 Beirut Barracks Bombing," is published this week, on Sept. 24, 2024, by Atria Books/Emily Bestler Books, a division of Simon & Schuster — and readers of Fox News can catch an exclusive preview ahead of the official release.

"Those who have read my James Reece ‘Terminal List’ series or who follow me on social media know the importance I place on history, particularly the history of warfare, terrorism, insurgencies, counterinsurgencies and special operations," Carr previously told Fox News Digital in an interview.

JACK CARR, BESTSELLING AUTHOR AND FORMER SEAL, ANNOUNCES NONFICTION SERIES, ‘TARGETED,’ ON TERROR EVENTS

The terror attack on the Marine Corps barracks in Beirut in Oct. 1983 killed 241 U.S. military personnel, including 220 Marines, 18 sailors and three soldiers. Another suicide bombing just moments afterward killed 58 French paratroopers; six innocent Lebanese civilians were also killed.

Here is an exclusive excerpt from the new book about the devastating attack — 41 years ago this fall — by Jack Carr and James M. Scott. It's already been deemed "required reading" by reviewers.

Exclusive excerpt from ‘Targeted: The 1983 Beirut Barracks Bombing’ by Jack Carr and James M. Scott

The first light of dawn stretched across the Beirut sky at 5:24 a.m. that Sunday, Oct. 23, 1983.

Colonel Geraghty climbed out of his bunk a few minutes later, pulled on his uniform and boots, and washed his face with cold water.

The Marine commander lived on the second deck of what had once been the airport’s firefighting school, a two-story concrete structure in the shadow of the much larger building that now housed the Battalion Landing Team headquarters.

Geraghty walked downstairs to the Command Operations Center, where he checked in with the watch officer and thumbed through the latest communications.

"Saturday night," he recalled, "had been, by Lebanese standards, relatively quiet."

The colonel stepped outside, where the morning temperature hovered around seventy-seven degrees. A few Marines returned from patrol while a handful of others prepared for physical training. It was almost tranquil. Reveille, which normally blared at 5:30 a.m., would sound at 6:30 a.m., giving troops an extra hour of shut-eye.

"Sunday is my favorite day," Hudson once declared, "because I get to sleep as late as I want." Brunch would follow from 8 a.m. until 10 a.m., a treat that included omelets.

The Navy Broadcasting Service planned a 1:55 p.m. showing of the Los Angeles Raiders versus the Washington Redskins — a game that had played live twenty-one days earlier — followed that evening by the 1960 Western "The Magnificent Seven," starring Yul Brenner and Steven McQueen.

"Sunday was normally the day people could anticipate reading a book, writing a letter, or passing a football around," remembered Staff Sergeant Randy Gaddo. "Later in the afternoon, everyone would normally enjoy a cookout, featuring hamburgers and hot dogs with all the trimmings."

Gaddo was one of the few up early. Even though it was Sunday, the "Root Scoop" editor had eight rolls of film he wanted to develop in his photo lab up on the third floor of the Battalion Landing Team headquarters.

The previous eight-page newspaper, which had landed among the troops just three days earlier, featured a roundup of the escalating sniper attacks against American forces, including the recent killing of Soifert and Ohler and the wounding of eight others.

In the weekly "Chaplain’s Corner" column, Father George Pucciarelli drew from the Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes to offer comfort for the Marines in these dangerous times.

"Life is dear," the priest reminded readers, "but eternal life is dearer."

Gaddo left his tent for the headquarters building, a route he had done so many times that he knew it took him just fifty-one seconds. Like Geraghty, he noted the quiet; absent was the normal soundtrack of artillery and gunfire.

At the last moment, Gaddo decided to slow down. It was, after all, Sunday morning. Why rush?

JACK CARR'S TAKE ON THE 1983 BEIRUT MARINE BARRACKS TERROR ATTACK: ‘OPENING SALVO IN A NEW WAR’

Besides, he could use a cup of coffee. He diverted to the Combat Operations Center, where he poured a mug of dark brew, sweetening it with a couple of scoops of sugar. Coffee in hand, he returned to his tent, where he sat at his small field desk and began to jot down notes.

"The birds were singing louder than I’ve ever heard birds sing," Gaddo recalled. "It was like a symphony."

Lance Corporal Burnham Matthews had just returned from an all-night security patrol around the south side of the airport, where the Marines had fanned out along the perimeter to intercept anyone who might infiltrate the compound.

The towering Texan climbed three flights of stairs and turned left toward the third-floor room he shared with five other Marines on the building’s north side, anxious to collapse on his cot.

Once inside, Corporal Kenny Farnan, who was headed downstairs to shave, pointed to Burnham’s M16.

"Your rifle is filthy," he advised him. "You need to clean your rifle before you go to bed."

"Okay, Corporal," Matthews replied, sitting down at the wooden desk by the window, where he began to field-strip his M16, beginning with the rifle’s sling.

Followed by the handguards. Then the bolt assembly.

In the room next door, Sergeant Pablo Arroyo was also up and cleaning his rifle. "You don’t know," the native Puerto Rican said, "what the day is going to bring."

Unlike Matthews and Arroyo, most of the 350 Marines, sailors, and soldiers crowded inside the towering Beirut Hilton still slumbered. The men dozing in military-issued sleeping bags came from a wide range of cultural and religious backgrounds.

Troops hailed from big cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Dallas as well as small towns, from Michigan’s Fire Lake to Little Mountain, South Carolina, home to just 282 residents.

Some had grown up on sprawling farms while others came from congested inner-city public housing projects. Education ranged from high school to medical school.

The building, and the men dreaming in it, represented a cross-section of America. Traces of the men’s lives were captured in photographs of wives, girlfriends, and children taped to concrete walls and tucked inside worn wallets.

Chaplain Wheeler, who had baptized First Sergeant David Battle the day before, snoozed in his fourth-floor bunk in the northeast corner of the building. Steps away on the same floor, Hudson slept as he always did, with his right hand over his face, palm facing upward.

Down on the second floor dozed Lance Corporal Emanuel Simmons, who had gone to bed the night before dressed in his boots and flak jacket. When he woke up in the middle of the night to use the head, he opted to strip down to just his long underwear.

Up on the building’s roof, Corporal Joseph Martucci and others stretched out in sleeping bags, while five stories below in the building’s basement, Hospital Corpsman Third Class Don Howell resisted the urge to find a urinal as he tried to grab just a few more minutes of quiet atop a cot in the Battalion Aid Station.

A late-night alert had sent Howell to the basement. After the all-clear, he had decided to remain where he was instead of hiking back up to his fourth-floor bunk.

Throughout the building, many of the Marines, who disliked sleeping in uncomfortable dog tags, had slipped them off, depositing them on bedside tables, dangling them from the edge of their cots, or lacing them up in the front of their dusty boots.

Security that morning fell to a handful of guards stationed at seven outposts that encircled the compound. Lance Corporal Eddie DiFranco manned post six, one of two sandbagged positions that protected the south side of the building.

Linkkila, recently promoted to a lance corporal, guarded neighboring post seven approximately forty feet away. A row of concertina wire divided the Marine compound from an adjacent airport parking lot, which was often used by delivery trucks and civilians, including kids who played soccer and families who occasionally picnicked.

On the weekends, many Marines liked to strip off their shirts and toss the football alongside the barbed wire, hoping to impress the attractive Lebanese women who gathered on the opposite side. Dressed in helmets and flak vests, the Marines, who had been on duty since 4 a.m., carried night-vision goggles and M16s.

JACK CARR'S TAKE ON THE 9/11 TERROR ATTACKS — INCLUDING ‘HOPE’ AND THE LESSONS FROM AFGHANISTAN

To prevent accidental discharges, Colonel Geraghty had ordered his men to keep their rifles unloaded.

It had been an uneventful morning for the guards. The only activity was the brief appearance of a lone stake-bed truck. It had entered the parking lot with its lights off around 5 a.m.

The truck looked like a delivery vehicle and was a common sight in Beirut, particularly near the airport. It circled the lot and departed, continuing south down the perimeter road toward the terminal.

The guards relaxed.

Thirty more minutes passed. Then an hour.

Corporal Farnan emerged from the building. Dirty and sweaty after being out all night, he walked over to the water buffalo, a portable trailer where he could brush his teeth and shave.

"That’s the first time," Farnan recalled, "that I ever left my rifle behind."

Shortly past 6:15 a.m., a second truck pulled into the lot, which the morning light revealed to be a yellow Mercedes. It appeared to be a similar vehicle, if not the same truck that had entered and then departed the lot an hour earlier.

The truck turned west, paralleling the concertina wire, as the driver, like before, looped the lot. Unlike earlier, DiFranco heard the rev of the Mercedes’s engine as the operator shifted into a higher gear and increased speed.

The driver then executed a sharp turn north and aimed his five-ton truck straight toward the wire barrier. Something felt wrong.

DiFranco rammed a magazine into his rifle and chambered a round as the truck crashed through the barbed wire, producing a popping noise that survivors would later tell investigators resembled gunfire. The Mercedes accelerated, charging across the 450 feet that separated the concertina wire from the building.

JACK CARR'S TAKE ON TERRORISM IN THE SKIES ON JUNE 14, 1985: CREW WAS ‘NOTHING SHORT OF HEROIC’

Before DiFranco could shoulder his M16, the truck blew past him, the operator gripping the wheel with both hands.

"I caught only a glimpse of the driver as he passed by," DiFranco wrote in a handwritten memo for investigators. "He was wearing a blue shirt and had the smile of a crazy person on his face when he looked at me."

In nearby post seven, Linkkila had only briefly served as a guard, his punishment for getting into a fight. His first sign of trouble came when the truck tore through the wire, but like DiFranco, he simply couldn’t load his rifle fast enough.

"I would have emptied the magazine into the truck," he later testified to Congress, "but there wasn’t any time."

Sergeant of the Guard Stephen Russell manned the building’s entrance in a plywood shack reminiscent of a ticket booth, though reinforced with a double wall of sandbags.

The twenty-eight-year-old Massachusetts native, who had followed his two older brothers into the Marine Corps, had been on duty since 8 p.m. the night before.

His M16 was propped against the wall of his guard shack. He wore a 1911A1 .45-caliber pistol on his web belt. Russell faced the inside of the building as he chatted with a fellow Marine who was about to head out for a jog when he heard the commotion behind him.

He wheeled around as the truck threaded a path between guard posts six and seven and then swerved around several metal sewer pipes that had been strategically placed in an attempt to prevent just such an attack.

Follow Jack Carr on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/jackcarrusa

The Mercedes, now traveling in excess of thirty-five miles per hour, bore down on him.

"What is that truck doing inside the perimeter?" he thought.

Then he realized.

"Get the f--- outta here!" he hollered at the Marine next to him.

JACK CARR RECALLS GEN. EISENHOWER'S D-DAY MEMO ABOUT ‘GREAT AND NOBLE UNDERTAKING’

Russell served as the last line of an impossible defense — one man armed with a handgun standing between a terrorist in a five-ton truck bomb and hundreds of sleeping Marines and sailors. There was nothing he could do.

"Hit the deck!" Russell shouted as he charged out of his guardhouse and raced north across the building’s atrium. "Hit the deck!"

Farnan, who seconds earlier had washed his face, darted toward the building but instinctively stopped. "I just watched it go in," he remembered. "Went right in the lobby."

Russell looked back over his shoulder as he ran to see the Mercedes obliterate the guard shack and penetrate the building’s atrium, spraying sand across the floor of the lobby. The truck came to a sudden stop, snagged on the atrium’s overhang. Silence followed. One second turned to two.

"Son of a b----," Russell said of the terrorist. "He did it."

The clock in the basement recorded the precise moment of detonation: 6:21:26 a.m.

The entire attack had taken just ten seconds.

The blast, which investigators later determined exceeded 12,000 tons of TNT, proved more than six times as powerful as the one used against the American Embassy in April.

"The FBI Forensic Laboratory," a Pentagon report later noted, "described the bomb as the largest conventional blast ever seen by the explosive experts community."

For those on the ground, the split-second detonation, which would kill and maim hundreds, proved unimaginable.

"It was," as one survivor later recounted, "like every atom in the universe blew apart."

The destruction was immediate and catastrophic. The building’s open internal architecture, capped by a roof that functioned like the cork on a champagne bottle, trapped and magnified the devastating violence. The explosion blew out the bottom of the building, driving the concrete slab eight feet into the earth.

At the same time, the blast tore the upper three floors off the concrete support columns, each with a fifteen-foot circumference and supported by 13⁄4-inch iron rebar.

"The building," one report concluded, "then imploded upon itself and collapsed toward its weakest point — its sheared undergirding."

Up on the roof, Corporal Martucci, who had heard the initial furor far below, started to sit up in his sleeping bag just as the bomb exploded.

"We saw the center of the roof actually lift, blow out," the corporal recalled. "We had wrapped ourselves in our sleeping bags; I guess it was instinct due to the noise, but we rode the roof down after that."

Sergeant Arroyo, cleaning his rifle on the third deck, heard what he thought was gunfire, a common sound in the Lebanese capital.

"It’s Beirut," he said to himself. "That’s like a rooster croaking in Puerto Rico in the morning."

Next door, Lance Corporal Matthews caught the commotion as he reassembled his M16. "There is something going on," Matthews hollered to another Marine in his room. "Wake everybody up."

Matthews never heard the bomb’s explosion, but he saw a bright orange flash as the escaping rush of pressure tore the door off its hinges, lifted him out of his chair, and hurtled him through the window. Matthews flipped over once in the air and then landed on his feet three stories below, where he collapsed and rolled to a stop.

He climbed back up onto his feet. "I turned around and looked," Matthews remembered, "and the building was gone."

Matthews was one of the lucky ones.

The explosion had thrown him clear of the building, where, like an accordion, the fourth floor had collapsed upon the third, followed by the second, and then the ground floor.

Corporal Farnan was one of the few to witness the building’s disintegration. The blast pressure had ripped his shirt off, knocked the wind out of him, and tossed him against a nearby curb.

He struggled to breathe as concrete fragments rained down on him and a cloud of dust rose into the sky.

"I was in the eye of a hurricane," Farnan said. "I can’t believe I wasn’t killed."

Hundreds of Marines and sailors lay buried beneath the rubble of a building that seconds earlier had been their home.

Many were dead, crushed under tons of pancaked concrete and rebar — men who had gone to sleep, never to wake up.

For more Lifestyle articles, visit www.foxnews.com/lifestyle

Others, however, had survived, trapped beneath cots, desks, and toppled walls that for the moment shielded them from the onerous weight of the wreckage.

Hospital Corpsman Don Howell, on a cot in the basement, heard what sounded like the roar of a freight train as the building came down on top of him.

A piece of concrete struck him in the right eye.

"It felt like a boulder," he said. "That’s when I turned around and tried to cover my head."

TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

Lance Corporal Simmons, who had been asleep on the second floor, struggled to understand what happened.

"I never heard the blast, never felt myself falling," he said. "I couldn’t see anything and all I felt was dirt."

Chaplain Wheeler, who had been asleep on the fourth floor, experienced the same.

"I didn’t hear anything," he remembered. "Next thing I knew, I woke up below the floor and below the debris — buried. That’s when I first realized things weren’t right. I was pinned. I couldn’t move. I didn’t know what happened."

The clock now ticked on their survival.